Aaron broke barriers during rise to Majors

A model of this story initially ran in January 2021.

Jackie Robinson built-in the National League in April 1947. Larry Doby built-in the American League three months later. As monumental and consequential as these debuts have been, segregation remained a actuality in skilled baseball — and American life, basically — for a few years afterward.

That actuality was significantly pronounced within the Deep South, the place Jim Crow legal guidelines nonetheless dominated the land and racial tensions have been deeply rooted. And the South Atlantic League (or “Sally League”), which had groups in such segregation strongholds as Knoxville, Tenn.; and Savannah, Macon, Columbus and Augusta, Ga.; posed a deep problem for integration efforts.

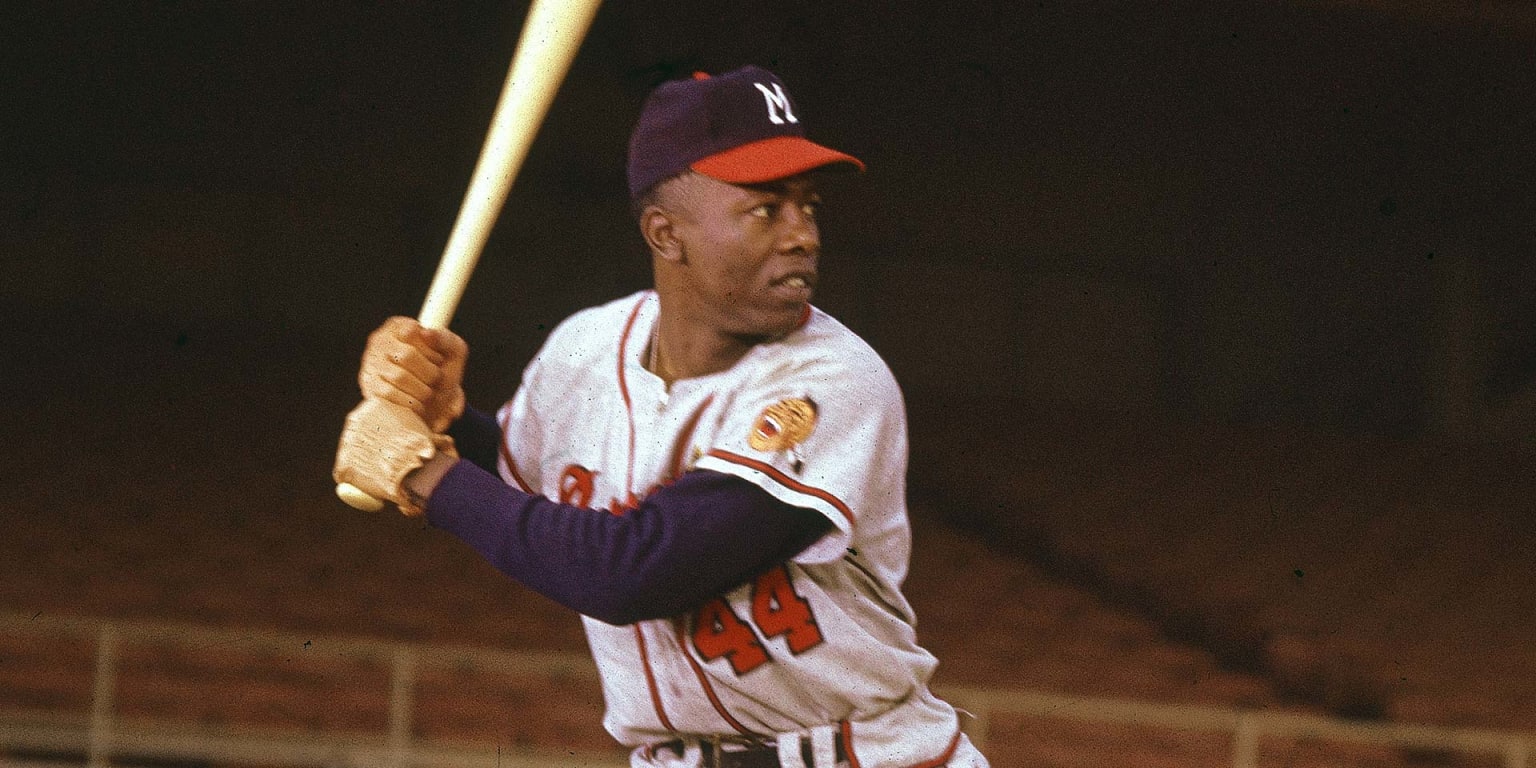

This is the problem that 19-year-old second baseman Hank Aaron and two fellow gamers within the Braves’ Minor League system — shortstop Felix Mantilla and outfielder Horace Garner — confronted in 1953, after they have been assigned to the franchise’s Class A affiliate in Jacksonville, Fla. Along with two gamers from the Athletics’ Savannah squad — Buddy Reedy and Al Isreal — they broke the colour barrier in essentially the most infamous of the white Minor Leagues.

It is a vital, usually ignored piece of the late Aaron’s monumental legacy.

“Henry would have a more difficult time even than Robinson,” creator Howard Bryant argued in “The Last Hero,” his biography of Aaron. “Where Robinson would take pleasure in going to his residence ballpark in Brooklyn half the time, the Sally League would play all of its video games within the Deep South. Even the house park, Jacksonville, wouldn’t all the time be a pleasant place.

“Henry knew he might be able to win over the home fans with spirited play, but off the field, he found that Jacksonville was another southern town that was not ready to treat him with any degree of humanity.”

Jacksonville’s group, beforehand often known as the Tars, was newly affiliated with the Braves and took on the nickname of the Major League membership, which itself was new to Milwaukee that season. So integration was a part of an general change happening.

From what we all know of Aaron’s 1952 season, in Eau Claire, Wis., his .336 batting common was in all probability worthy of an even bigger promotion than the one which despatched him to Jacksonville. (Interestingly, the Braves’ Double-A group at the moment was in Atlanta, the place Aaron would, after all, go on to have his seminal baseball second.) But the membership opted to convey him alongside slowly, and the South Atlantic League would take a look at him in ways in which had nothing to do with baseball.

Having grown up in Mobile, Ala., Aaron was all too aware of what it meant to have darkish pores and skin within the Deep South. But for Mantilla, a Puerto Rico native of Afro-Puerto Rican descent, segregation legal guidelines and the language barrier have been new phenomena. He and Aaron shaped a friendship, and Aaron was instrumental in serving to Mantilla adapt to the difficulties.

“It was Hank who always kept me away from the things that could have gotten me in trouble,” Mantilla informed Bryant. “Hank and I relied on each other. We tried not to let the other out of our sight.”

By regulation, the three Black gamers weren’t permitted to dwell with their white teammates. And in order that they have been taken in by native business proprietor Manuel Rivera, who, like Mantilla, was of Afro-Puerto Rican descent. Some of their white teammates put themselves in peril by going out to dinner with them, typically with a baseball bat to scare off any aggressors.

The subject was a extra comfy place, however no sanctuary. Some “fans” would jeer Jacksonville’s black-skinned gamers and name them “alligator bait.”

“They wouldn’t boo you because you were playing bad,” Mantilla informed Sport Magazine in 1965. “It was just because you were colored.”

Aaron, Mantilla and Garner have been taught to disregard the vitriol, to shrug off unjust umpiring, to place their heads down and play. It was the code that Robinson and Doby and all of baseball’s Black pioneers have been compelled to comply with.

One day, nevertheless, Mantilla couldn’t convey himself to abide by these phrases. The Black gamers have been thrown excessive and tight pitches as a matter of routine, but a selected head-hunter of a pitcher named John Waselchuk — in a detailed recreation on an already heated July day by which followers have been jawing at one another within the segregated stands and police had arrived on the scene — set Mantilla off. Mantilla started to cost the mound and, had Garner not interjected and dragged his teammate to the bottom, the scenario might have gotten uncontrolled.

Race-related issue and discord didn’t cease Jacksonville, which till then had been a perennial basement dweller, from storming up the Sally standings. The Braves completed first, with a 93-44 file, and Aaron led the league with a .362 batting common and 36 doubles whereas rating second with 22 residence runs. He was named the South Atlantic League’s MVP, and he and Mantilla have been each All-Stars.

And that 1953 season was consequential off the sphere for Aaron, as effectively. Early within the 12 months, he met his first spouse, Barbara Lucas, a Jacksonville native and scholar at an area business college. The two married later that 12 months. (They divorced in 1971.)

The extra they received baseball video games, the extra Aaron, Mantilla and Garner received over the Jacksonville followers, however solely to some extent. Mantilla informed Bryant of a recreation by which he and Aaron had performed significantly effectively in a hard-fought victory and a white fan approached them afterward to congratulate them. But even then, the person referred to them by a racial slur.

So Jacksonville gave Aaron a style of what he would endure in his Major League profession, when the Braves moved from Milwaukee to Atlanta and, significantly, when he neared Babe Ruth’s profession residence run file and started to obtain an onslaught of hate mail and dying threats.

Playing in Old Dixie meant that Aaron couldn’t be simply one other ballplayer. Prejudice was part of his life and is part of his story. And whereas it’s Aaron’s sleek dealing with of the ugliness he endured through the Ruth pursuit that earns him standing as a Civil Rights icon, Jacksonville is part of the story that shouldn’t be ignored. For very similar to Robinson and Doby, Aaron skilled and understood the nice issue of crossing a baseball coloration barrier.