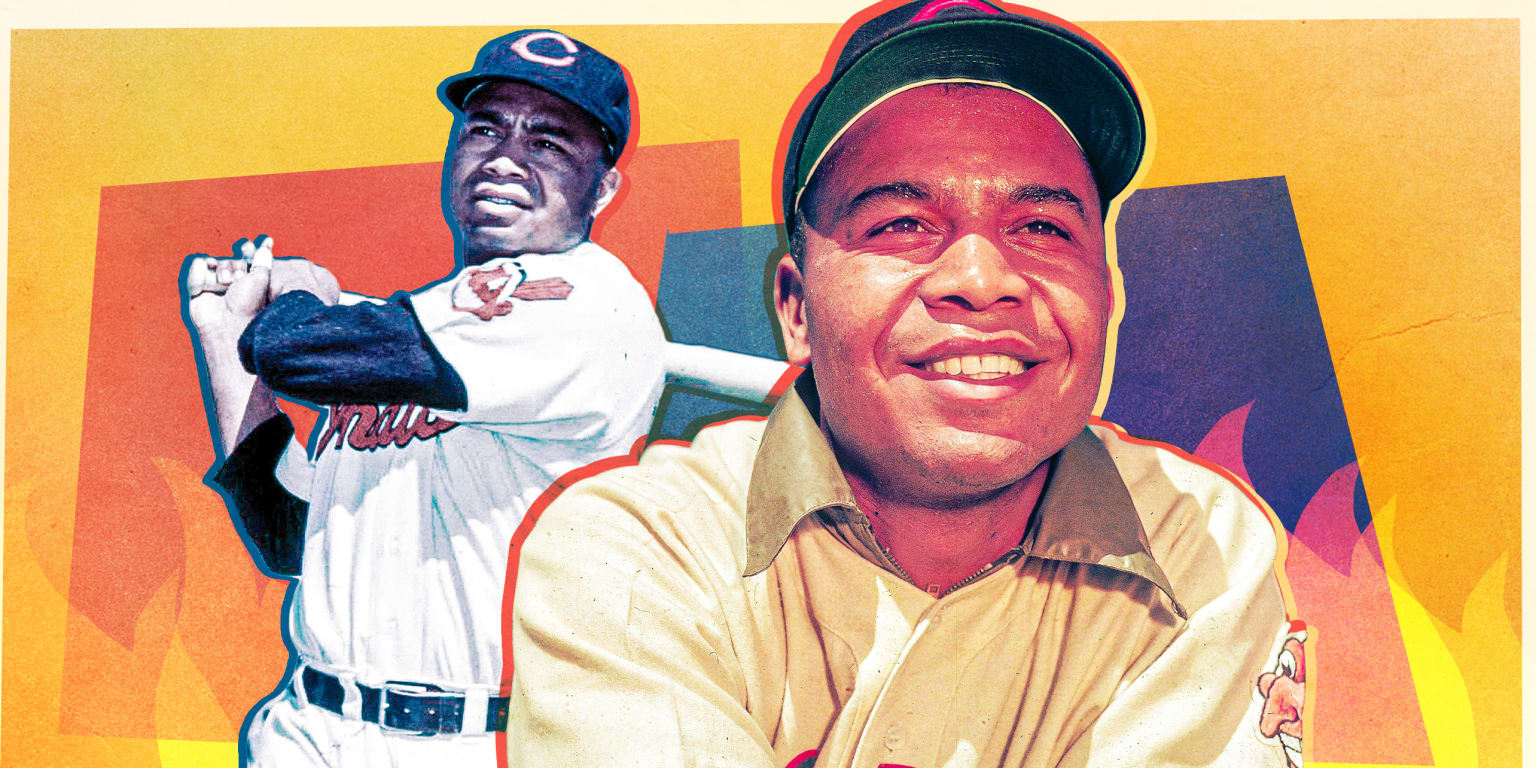

The crack-of-dawn call to Larry Doby that changed baseball

A model of this story initially ran on July 5, 2022, the seventy fifth anniversary of Larry Doby’s debut with Cleveland.

Larry Doby bought what shut-eye he might because the bus carrying him and his Negro League teammates made its trek from Wilmington, Del., to Newark, N.J., within the early morning hours of Thursday, July 3, 1947.

As Doby slept that night time 75 years in the past, he didn’t know in regards to the newspaper report bearing his title. Did not know that his dwelling would, in a matter of hours, be swarmed by inquiring reporters. Did not know that his life — and all the construction {of professional} baseball — was about to be enduringly altered.

By the time Doby had disembarked the bus, pushed his Ford convertible to his residence in Paterson, N.J., and gotten into mattress for a extra correct relaxation, it was roughly 5:30 a.m. And it was simply earlier than 7 a.m. when Newark Eagles proprietor Effa Manley rang Doby’s cellphone and lower quick his sleep with the large news.

“Larry,” she mentioned, “you have been bought by the Cleveland Indians of the American League and you are to join the team in Chicago on Sunday.”

While Jackie Robinson’s color-barrier-breaking debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers 11 weeks earlier was a cultural touchstone and an important precursor to the American civil rights motion, it is very important take into account what the acquisition of Doby’s contract meant not only for the now-integrated AL, however for baseball’s framework.

Robinson, in any case, had signed his contract with the Dodgers in October 1945, and spent all the 1946 season within the Minor Leagues with the Dodgers’ Triple-A affiliate in Montreal. He was promoted to the Majors six days earlier than the beginning of the 1947 season, unofficially debuting in an exhibition recreation at Ebbets Field 4 days earlier than the true factor.

Doby, however, arrived to the AL actually in a single day, on a Pennsylvania Railroad practice, to make his debut on July 5, 1947, in opposition to the White Sox.

So, one thing extra definitive was communicated by Doby coming to Cleveland. If Jackie was baseball’s experiment with integration, or the sowing of a seed, Doby was proof that the seed had taken root. There may very well be no denying now about what was occurring and what would occur. The dying knell had been sounded — bittersweetly — for the Negro Leagues, with one of the best Black gamers plucked and rostered and at last in a position to show their abilities on baseball’s largest stage.

“The entrance of Negroes into the Majors is not only inevitable,” Cleveland proprietor Bill Veeck informed a reporter when the Doby signing grew to become official, “it is here.”

The desegregated Major Leagues, which ought to have been in existence all alongside, was lastly going to occur.

And in Larry Doby’s case, it was going to occur quick.

It was a giant change to go from the Newark Eagles to the Cleveland Indians. But the sensation was not unfamiliar for a person who had grown up in a state of near-constant motion and upheaval.

Lawrence Eugene Doby was born on Dec. 13, 1923, in Camden, S.C., the son of a secure hand. His father, David Doby, fed and cared for the saddle horses of rich households, spending his summers in Saratoga, N.Y., and his winters in Camden. It was good work, however the frequent journey strained David’s marriage with Larry’s mom, Etta, who wound up shifting solo to Paterson to work as a maid.

That left Larry, whose nickname inside the household was “Bubba,” primarily underneath the care of Etta’s widowed mom, Augusta Brooks. She fed him, raised him and launched him to faith.

“She made me go to church with her all the time,” Doby informed biographer Joseph Thomas Moore. “I liked what I heard in the Twenty-Third Psalm [‘The Lord is my shepherd: I shall not want’] and the Ten Commandments. Somehow I got the feeling that the church helped Black people to be themselves. I liked that feeling.”

Augusta was so essential in Doby’s life that he didn’t even go by the final title Doby. In these early years, he glided by the title Bubba Brooks.

Young Bubba’s world was turned the other way up in the summertime of 1934, when he was simply 10 years outdated. His grandmother was hospitalized with dementia, forcing the kid to maneuver in with an aunt and uncle. That identical summer time, David Doby drowned after falling off a fishing boat on Lake Mohansic in New York. He was simply 38 years outdated.

For the primary 4 years after his father’s dying, Lawrence Doby — as he was now referred to, having embraced his actual first and final title — lived together with his Aunt Alice and Uncle James and their 5 youngsters. But when Doby completed eighth grade, his mom had him transfer to New Jersey, the place he would attend Eastside High School in Paterson’s built-in faculty system.

His mom’s schedule, which included only one “maid’s day off” per week, additional added to the challenges of Doby’s uncommon upbringing. Rather than truly reside together with his mother, Doby bounced from home to deal with, staying with Etta’s mates.

“I had been alone most of my life,” Doby informed Moore. “I had gotten accustomed to that. Not that I wanted to be alone. You learn to live with being alone.”

Doby was introspective and impartial. He was quiet and brooding, with a wholesome quantity of righteous anger at all times effervescent beneath the floor. It was a product of these unusual circumstances he had endured rising up.

Yet these circumstances and that character would serve Doby effectively when his athletic expertise put him in place to make baseball historical past.

The new second baseman on the Newark Eagles amazed folks together with his polished play. He arrived out of nowhere to bat .400 in the summertime of 1942 and was hailed by sportswriters as an “overnight sensation.” Signed by Newark co-owners Abe and Effa Manley for $300, this younger man from Los Angeles named Larry Walker clearly possessed the potential to dominate the Negro Leagues for a few years.

Except that Larry Walker from Los Angeles wasn’t actually Larry Walker from Los Angeles.

He was Larry Doby from Paterson.

Assigned an alias as a way to protect his beginner standing, Doby first suited up for Newark earlier than he even graduated highschool. The Manleys had been made conscious of an distinctive 18-year-old making waves on the baseball circuit, in order that they gave him a tryout on the down-low and wound up signing him to his first skilled contract. (That made him a baseball-playing “Larry Walker” lengthy earlier than the eventual Hall of Famer Larry Walker was born in Canada in 1966.)

It’s no shock that Doby would have attracted the curiosity of the Newark Eagles, as a result of he had been a marvel in 4 sports activities in highschool. And he knew what it meant to combine and infiltrate an all-white taking part in area lengthy earlier than he reached the American League.

In Paterson and within the different New Jersey industrial cities that had been dwelling to Eastside High’s rivals, Doby carried out amid many injustices. As the lone Black participant on his soccer staff, Doby, a large receiver, needed to preserve his cool when opponents piled on him and dug their knees into his again. He didn’t let it deter him. In his senior yr, Doby was a distinguished piece of Eastside High’s first state championship soccer staff, a basketball star too speedy and inventive to be guarded, and an achieved broad jumper in observe, breaking the convention report with an almost 21-foot bounce in his very first meet.

But he was at his very best on the baseball diamond. There, Doby ripped line drives, zipped across the basepaths and performed each place however pitcher and catcher, all whereas constructing upon his native superstar.

Doby’s standing was such {that a} dinner was held in his honor throughout his senior yr, with audio system reciting speeches and poems about his athletic feats. Doby was feted with a gold wristwatch and dubbed by the varsity’s coaches “the greatest athlete to ever represent Eastside High School, bar none.” And but, the one factor clearer than his expertise was the systemic limitation positioned upon it.

“He’d get four hits in a row or something,” teammate Al Kachadurian as soon as informed sportswriter Hank Gola, “and the kids would go home and say, ‘Too bad he’s Black.’ … We felt sorry for him.”

The Negro Leagues had been the one place Doby may very well be paid to play baseball, and the hush-hush stage title he used for elements of two seasons with the Eagles allowed him to maintain his faculty basketball scholarship — first at Long Island University earlier than transferring to Virginia Union. The association would have lasted longer had Doby not been drafted into the struggle effort in 1943. He was halfway by his second season with the Newark Eagles when he left to journey to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station exterior Chicago, the place the Black recruits had been separated from the white ones.

“This was the first time that segregation really stung me,” Doby later mentioned. “I wasn’t expecting it in the military. I had no idea. It hurt a lot.”

The identical segregation existed on army sports activities groups. Doby performed for the Black Bluejackets, a baseball squad of Black sailors. He was not even allowed to check out for the Great Lakes base’s more-heralded, all-white Bluejackets staff.

Doby did, nonetheless, safe a place as a Navy bodily schooling teacher. One of the “boots” he skilled in that position was none apart from Marion Motley, who, together with teammate Bill Willis in September 1946, would break skilled soccer’s colour barrier with the Cleveland Browns.

Even within the Navy, Doby’s baseball potential was clear. Years later, he would inform the story of Hall of Fame catcher Mickey Cochrane, who coached the white Bluejackets, pulling him apart and telling him, “If I was still managing in the big leagues, I’d want you on my side.” Doby additionally struck up a friendship with All-Star first baseman Mickey Vernon, who was a member of the white Navy squad and wrote to Washington Senators proprietor Clark Griffith imploring him to signal Doby.

Alas, Major League golf equipment weren’t but prepared to do proper by the good Black gamers of that period. So, when Doby’s time within the Navy ended within the spring of 1946, he returned to the Newark Eagles.

This time, Doby performed by his actual title.

And in 1947, that title would appeal to the eye of a sure massive league proprietor.

When Bill Veeck was a younger man in Chicago within the Nineteen Twenties and Nineteen Thirties, he attended dwelling video games of the Negro Leagues’ Chicago American Giants, in addition to the annual East-West All-Star video games that had been usually held at outdated Comiskey Park. He was the son of Chicago Cubs president William Veeck, and he grew up within the prosperous suburb of Hinsdale. But Bill Veeck’s curiosity in baseball was colorblind. Talent was expertise, and he encountered loads of it in his style of Black baseball. He knew the names, the positions and the stats of the Negro Leagues’ greatest and brightest.

That expertise undoubtedly knowledgeable what got here later. Veeck, who bought the Cleveland Indians in 1946, was not the primary proprietor to interrupt the colour barrier, however he was not far behind, both.

“What offends me about prejudice,” he wrote in “Veeck As in Wreck,” his autobiography, “is that it assumes an unwarranted superiority.”

In that very same e-book, Veeck claimed to have hatched a plan in 1942 to purchase the lowly Phillies and inventory their roster with Negro League stars, however that Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis intervened and ensured the sale would go as a substitute to lumber baron William D. Cox.

Historians have debated whether or not or not that exact declare by Veeck is true. But what’s simple is that Veeck didn’t help segregation. Earlier in 1942, when he was nonetheless the co-owner of the Triple-A Milwaukee Brewers, Veeck had sat within the “colored section” of the bleachers throughout Spring Training in Ocala, Fla., to talk with followers. When safety tried to get Veeck to depart and to respect the segregation ordinance, Veeck refused to again down. And when Ocala’s mayor was summoned to the scene, Veeck threatened to drag his staff out of the town for good.

That was Veeck’s method. He was an innovator who pushed again in opposition to the established order. Ordinarily, that attribute is referenced in relation to his many stunts — the exploding scoreboard or Grandstand Managers Day or sending the 3-foot-7 Eddie Gaedel as much as bat. But his strategy to the essential “innovation” of integration was sophisticated. Though open to it from the second he grew to become proprietor of the Cleveland Indians on June 22, 1946, Veeck progressed, in his personal later phrases, “slowly and carefully, perhaps even timidly” towards truly bringing a Black participant aboard.

By the time Veeck took over in Cleveland, Jackie Robinson was two months into his season with the Triple-A Montreal Royals, inching his method towards his seismic introduction to the NL. The Dodgers had additionally swiped Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe from Negro League rosters and put in them with their Class B Nashua membership in New Hampshire.

Meanwhile, Larry Doby was in his “rookie” yr (together with his prior contributions as “Larry Walker” not formally acknowledged) with Newark, starring for the Eagles as they stormed their method towards a Negro World Series title. Newark’s video games had been often attended by Clyde Sukeforth, the scout who had signed Robinson for the Dodgers. And Dodgers govt Branch Rickey even turned up at one.

There was little question that Doby, who married his spouse, Helyn, that very same summer time, was a focus.

“I think Larry is the best prospect in baseball,” Eagles proprietor Effa Manley wrote in a letter that summer time, “and can do all the things Jackie Robinson has done.”

That identical summer time, Veeck expressed to the Black sportswriter Cleveland Jackson that he would solely buy a participant from the Negro Leagues if it meant the “difference between a mediocre and a championship team for Cleveland.” And “mediocre” would have been a charitable method to describe a 1946 Cleveland membership that went 68-86 and completed sixth within the AL.

In the offseason, although, Veeck set about making the modifications that may make Cleveland a successful staff. And he grew to become severe about integration. In January 1947, he employed Bill Killefer, a former participant and longtime coach, to scout the Negro Leagues. Around that very same time, he employed a Black man named Louis Jones — a promoter and the primary husband of singer and actress Lena Horne — because the staff’s assistant director of public relations. Jones, subsequently, grew to become the primary Black govt in MLB, tasked with partaking with the town’s Black civic leaders and neighborhoods in preparation for the desegregation of the staff.

Cleveland was a wise place to have a Black participant within the massive leagues. It had been the house of Jesse Owens, the house of a championship Negro League franchise (the Cleveland Buckeyes gained the World Series in 1945) and the house of the built-in Browns, with the aforementioned Marion Motley and Bill Willis, within the All-America Football Conference. Add in a motivated proprietor in Veeck, and it was probably not a matter of when or if, however who.

Doby proved to be the reply.

Having already asserted himself within the Eagles’ championship run the earlier yr, Doby continued to construct on his profile with a terrific begin to the 1947 season. Sukeforth, the Dodgers scout, felt Doby would want a few years within the Minors earlier than he was prepared for the large leagues. But Killefer filed a way more direct scouting report.

“[Doby] can play in this league,” the report learn. “I don’t know whether he belongs in the infield or the outfield, but he can play.”

Veeck additionally had at his disposal the report of Louis Jones, who had appeared into Doby off the sphere and concluded he had the character to deal with such a transfer. Jones famous that Doby didn’t drink, swear or smoke.

Doby had his personal “scouting report” of his talents. When Jones visited him in June of 1947 and took him to a recreation between the Yankees and Cleveland at Yankee Stadium, Jones requested Doby if he felt he might maintain his personal in opposition to the gamers they had been watching on the sphere beneath.

“There’s nothing down there I can’t do,” Doby informed him.

Veeck was prepared to let Doby attempt. He felt the lengthy course of by which Robinson went from signing with the Dodgers within the fall of 1945 to truly taking part in for them in 1947 was unfair to Robinson, in that it solely added to the stress positioned upon him. Furthermore, he didn’t need to topic Doby to taking part in on the membership’s Double-A affiliate in Oklahoma City or its Triple-A staff in Baltimore, two cities the place a Black participant would possibly face notably robust vitriol.

And anyway, Veeck needed to win. He felt Doby might assist him do exactly that.

The name from Bill Veeck to Effa Manley was made on July 1, 1947. Unlike Rickey and the Dodgers, who pilfered Black gamers from their Negro League rosters with out compensating the membership homeowners, Veeck honored the validity of Negro League pacts and made Manley a proposal of $10,000, with an extra $5,000 if he stayed with the staff for greater than a month.

Unbeknownst to Doby that day, the Manleys accepted Veeck’s supply. But quickly, rumors of the deal started to develop. The following day, July 2, reporters from the Black newspapers approached Doby after the Eagles’ victory over the Philadelphia Stars in a recreation performed in Wilmington and requested him if these rumors had been true.

“It may be,” Doby mentioned, “but I don’t know until I get back to Newark.”

Back in New Jersey, nonetheless, the news was already popping out. An inquisitive reporter named Bob Whiting at Paterson’s Morning Call had adopted up on his hunch that Cleveland was near signing Doby and gotten affirmation of the deal. The news was rolling off the printing press because the Eagles’ bus rolled again to the Garden State.

That scoop by Whiting accelerated what would have already been a fast bounce to the large leagues for Doby. Had Veeck’s unique plan performed out, Doby would have a minimum of had a number of days to soak up this dizzying improvement earlier than suiting up for his new staff. The MLB All-Star break was approaching, and Veeck needed Doby to debut in Cleveland on July 10, within the first recreation of the second half.

Now, nonetheless, the Doby plan was put in fast-forward. Manley known as Doby with the official news at 7 a.m. on Thursday, and Doby was out there off the Cleveland bench simply over 48 hours later.

In between, although, Doby went out with a bang in Newark. On the afternoon of July 4, the Eagles performed a doubleheader at dwelling. Prior to the primary recreation, they put collectively an impromptu ceremony saluting Doby and sending him off with modest however significant presents — a shaving package, a journey case and a verify for $50. Doby, true to type, walloped a house run within the sixth inning of the primary recreation, which was a win for the Eagles. Rather than stick round for the second, he showered, modified and rushed to catch the in a single day Pennsylvania Railroad practice to Chicago at Newark’s Penn Station.

This was Larry Doby’s mad sprint into the historical past books. At some level within the whirlwind, the then-23-year-old remarked to the Associated Press that he didn’t know whether or not he was “more surprised than excited or more excited than surprised.” Privately, on the practice, he confessed nerves to his Helyn, remarking that he felt like he was venturing into “a new and strange world.”

Doby entered that world round 10:45 a.m. on July 5, when his practice arrived at Chicago’s Union Station. Escorted by Jones, Doby bought in a taxicab that then picked up Veeck on the Congress Hotel. (Doby himself must keep not on the staff resort however on the DuSable Hotel, a predominantly Black lodging on the town’s South Side.)

“Lawrence, I’m Bill Veeck,” the proprietor launched himself within the cab.

“Nice to meet you, Mr. Veeck,” Doby replied.

“You don’t have to call me Mr. Veeck. Call me Bill.”

Thus started an earnest friendship that may final for the rest of the lives of each males. Just as Rickey had carried out for Robinson, Veeck laid out the bottom guidelines Doby must comply with to stay within the Majors. Doby must chorus from arguing with umpires or preventing with opposing gamers, and he must endure no matter terrible barbs got here his method with persistence and with calm.

Doby was whisked on to a press convention at Comiskey, the place he signed his official contract and responded to questions from reporters in a hushed and nervous tone.

“Just remember,” Veeck informed him inside earshot of the scribes, “they play with a little white ball and a stick of wood up here just like they did in your league.”

But the distinction between the respect Doby commanded in Newark and the chilly shoulder he obtained from some within the Cleveland clubhouse — to say nothing of opponents — simply 24 hours later couldn’t have been extra stark.

After the press convention was over, Doby was guided to his locker, the place he donned the Cleveland uniform for the primary time. Manager Lou Boudreau led him across the quiet room and launched him to every of his new teammates, a few of whom greeted him less-than-enthusiastically, with limp handshakes or an absence of eye contact. In Doby’s telling, two teammates — first basemen Les Fleming and Eddie Robinson, each of whom had been at risk of shedding taking part in time to Doby — turned their again to him utterly. (Robinson would insist in his later years that his frosty remedy of Doby was due to the playing-time side and never race.)

When the Cleveland gamers trotted out to the diamond for pregame warmups, Doby discovered himself with out a catch accomplice. He stood exterior the dugout, humiliated, for mere minutes that felt like an eternity. In that second, these emotions of loneliness that had pervaded Doby’s youth sprouted up once more. But when, in the end, All-Star second baseman Joe Gordon tossed him a ball, Doby encountered his first participant ally in his integration.

That afternoon, Cleveland trailed, 5-1, coming into the seventh inning, when Doby was summoned with one out and two aboard to pinch-hit for pitcher Bryan Stephens. A crowd of blended race cheered his arrival to the plate as he nervously dug in.

“I didn’t hear a sound,” he later recalled. “It was like I was dreaming.”

Doby swung and missed at White Sox pitcher Earl Harrist’s first providing, then fouled off the following. He let the following two pitches go for balls however swung by the fifth pitch to go down with the Okay.

“Well,” Boudreau informed him upon his return to the dugout, “now you know some of what it is all about. You are now a big leaguer.”

The strikeout was emblematic of Doby’s first partial season within the AL. He appeared in 29 video games, made 33 journeys to the plate and hit simply .156 (5-for-32). Consider the whirlwind, the circumstances and the hate that he, like Robinson, confronted (“Nobody said, ‘We’re gonna be nice to the second Black,’” Doby as soon as mentioned), and people early struggles in a part-time position are comprehensible. The night time of his massive league debut, Doby was the one member of the Cleveland membership staying on the DuSable. He had no teammates to open up to or evaluate notes with. Doby was alone but once more.

But he had been raised to endure powerful occasions and harsh modifications. Just as Doby didn’t let his odd upbringing lead him down the fallacious path, he didn’t let the strikeouts, the segregated resorts, the “whites only” taxicabs, the insults, the slurs or the time he was spat on whereas sliding into second base deter him from his goals.

In 1948, Doby, blocked at second by Gordon, was tasked by Veeck with shifting to heart area as a way to carve out an everyday spot within the lineup. The place change solely added to the 24-year-old’s full plate. But the flexibility that served Doby effectively as a four-sport athlete in highschool additionally served him effectively within the transfer to the outfield. His bat caught on that yr, too. With the assistance of Doby’s .301 common, 14 homers, 23 doubles and 9 triples, Cleveland captured its first AL pennant in 28 years. And Doby’s 7-for-22 displaying within the World Series in opposition to the Boston Braves — together with what turned out to be the game-winning dwelling run in Game 4 — was instrumental in claiming what nonetheless stands because the franchise’s most up-to-date championship crown.

From that time on, there was by no means once more a doubt as as to if Doby might make it within the Majors.

He was chosen to the AL All-Star staff yearly from 1949-55 and completed within the prime 10 of the MVP voting in 1950 and 1954. After his taking part in profession, he grew to become a scout and a coach earlier than Veeck, who by this level was proprietor of the White Sox, known as upon him once more in 1978 by making him MLB’s second Black supervisor, behind Cleveland’s Frank Robinson three years earlier. As was the case in his AL debut, Doby was thrust into that obligation in the course of the season.

To be second, Doby discovered, is to be typically underappreciated. He went 39 years between his ultimate recreation as a participant in 1959 and his rightful induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1998 — an honor that got here simply 5 years earlier than his dying from most cancers at age 79.

Doby, although, set a template that not even Robinson might declare, for he was the primary Negro Leaguer to leap straight into the large leagues. Imagine being cheered lustily at some point at a ceremony in your honor after which having a teammate deny you a handshake the very subsequent.

For his half, Doby was glad to have had so little time to organize for the “new and strange world” he penetrated.

“I look at myself as more fortunate than Jack,” he as soon as mentioned of Robinson, with whom he grew to become shut. “If I had gone through hell in the Minors, then I’d have to go through it again in the Majors. Once was enough!”

There was just one Lawrence Eugene Doby. No, he was not MLB’s first Black participant. No, he doesn’t have a day wherein all the league wears his No. 14, as they do for Jackie and his No. 42 every April. No, he’s not the topic of dozens of books or a characteristic movie. And no, he was not saluted as a first-ballot Hall of Famer.

But this a lot have to be mentioned and understood in regards to the man whose legacy is simply too usually uncared for: The name got here, rousing him from sleep and welcoming him to do one thing that had by no means been carried out. And to the good thing about the numerous who adopted in his footsteps, Doby answered.