How Indigenous-led conservation could help Canada meet its land and water protection targets | 24CA News

In the far northwest of Manitoba, the Seal River flows 260 kilometres by the thick boreal forest into Hudson Bay. It’s the one main river in northern Manitoba with none dams. No roads result in the river, and there is just one human settlement within the river’s watershed.

That group, the Sayisi Dene, is main an initiative together with neighbouring Dene, Cree and Inuit communities to guard the 50,000 sq. kilometres of the watershed. That’s an space of untouched wilderness roughly the dimensions of Nova Scotia, which might be protected against industrial improvement if the group’s proposal is accepted.

“It is 99.97 per cent pristine. The watershed is actually fully intact. There are no disturbances, no industrial development in the watershed whatsoever,” mentioned Stephanie Thorassie, govt director of the Seal River Watershed Alliance.

“And for those reasons, because of how remote we are, we are a little piece of heaven in the world that is a little bit unnoticed and we kind of like it.”

The federal authorities has famous that Indigenous-led proposals just like the Seal River Watershed are essential for Canada to satisfy its conservation objectives. Canada has pledged to guard 30 per cent of its land and 30 per cent of its oceans by 2030. By the tip of 2021, about 14 per cent of every had been protected, in accordance with Environment and Climate Change Canada.

With the UN biodiversity convention, COP15, kicking off in Montreal this week, Canada has been behind a diplomatic push to attain a brand new international settlement on defending nature.

And consultants say consideration will probably be on Canada’s personal targets. In simply eight years, Canada has to double the quantity of land protected in the entire nationwide parks, provincial parks, conservation areas and different protected areas that had been established over the previous century.

While it is a tall order, crucially, it is also an opportunity to do conservation proper, by selecting essentially the most ecologically vital locations and letting Indigenous data and other people take the lead, in accordance with James Snider, the vice-president for science, data and innovation at World Wildlife Fund Canada.

“It’s through the lens of Indigenous-led conservation, or conservation more broadly, that supports Indigenous rights and objectives, that is the means by which we get to those important targets,” mentioned Snider, who has been researching essentially the most carbon-rich and ecologically precious areas within the nation over the previous 12 months.

Reconciliation by conservation

The historical past of the Sayisi Dene vividly illustrates this chance.

In 1956, based mostly on flimsy and in the end disproved proof, the Manitoba and federal governments determined that the caribou herd was declining, and blamed the Sayisi Dene for over-hunting. The complete group of about 250 folks had been relocated to only outdoors Churchill, on Hudson Bay, far-off from the lands that had sustained them for hundreds of years.

There, they skilled poverty, racism and lack of ample housing. Nearly half the group died after the compelled relocation, whereas the caribou inhabitants was finally discovered to be truly secure.

In 1973, a bunch of group members left on foot and settled round Tadoule Lake, within the Seal River watershed, to return to their conventional lifestyle.

Today, 325 folks dwell in the neighborhood. The Sayisi Dene survived by returning to their conventional homelands and life, however some say they are able to go additional.

The Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA) that they’ve proposed will — not like the false environmental issues that displaced them — present a brand new scientifically and culturally knowledgeable means of defending biodiversity, in accordance with Thorassie. It can even permit the group to supply employment by eco-tourism, she added.

WATCH | From the archives, the Sayisi Dene in Tadoule Lake:

The Sayisi Dene had been uprooted from their conventional caribou searching grounds in northern Manitoba and forcibly relocated, beneath the pretext of conserving caribou herds. This 1978 archival CBC story appears to be like at their lives in Tadoule Lake, Man., the place they finally ended up.

“I think that utilizing our first peoples to do this work is the right way to go about creating protected spaces,” Thorassie mentioned.

“Utilizing the knowledge of our elders and our community members and our land users — that knowledge that they carry is older than universities. It’s been here since before Canada was created.

“Being capable of have a possibility to face and inform the world what’s vital to us, for our causes, and to guard it for ourselves, by ourselves, is one thing that hasn’t been completed earlier than. That’s what’s totally different this time round.”

According to a report from the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS), Canada can nearly reach its conservation goal for 2030 with all the dozens of IPCAs already proposed across the country. But provincial governments have to be on board before an area can be protected, and the CPAWS report called out several provinces for dragging their feet on the process.

The report pointed out that Manitoba does not currently have a conservation target. About 11 per cent of the province is protected. But proposals on the table, which include Seal River, and a few other IPCAs, would get the province to 29.1 per cent, according to the report.

“We have monumental management on the bottom from Indigenous peoples who’re figuring out areas for cover throughout the nation,” said Alison Woodley, senior strategic advisor at CPAWS.

“But we’ve this blockage by way of provinces and territories which aren’t stepping up normally to truly undertake and embrace these bold targets and help Indigenous-led conservation.”

Canada’s newest national park

Canada’s newest national park, Thaidene Nëné National Park Reserve, is considered a success story. It was established in 2019 along the eastern arm of Great Slave Lake in the Northwest Territories.

It’s part of a larger Thaidene Nëné Indigenous Protected Area, which protects species like moose, bears and wolves, preserves habitat for various migratory birds and protects areas of boreal forest and tundra.

The national park and surrounding areas are co-managed by the government and the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation. Along with protecting the ecologically sensitive area, the Indigenous community’s vision is to provide employment to community members who will work as guardians and in other job roles in the park, develop infrastructure for visitors and work on conservation and research projects in the area, according to the community’s website.

Steven Nitah, the nation’s chief negotiator for the establishment of the national park, said that not all governments and jurisdictions are at the same level of understanding around Indigenous reconciliation, leaving challenges for other communities that want to establish IPCAs.

“Indigenous nations which can be advancing their very own protected and conserved areas actually must drive their agenda,” he said. “They must personal what they need to create.”

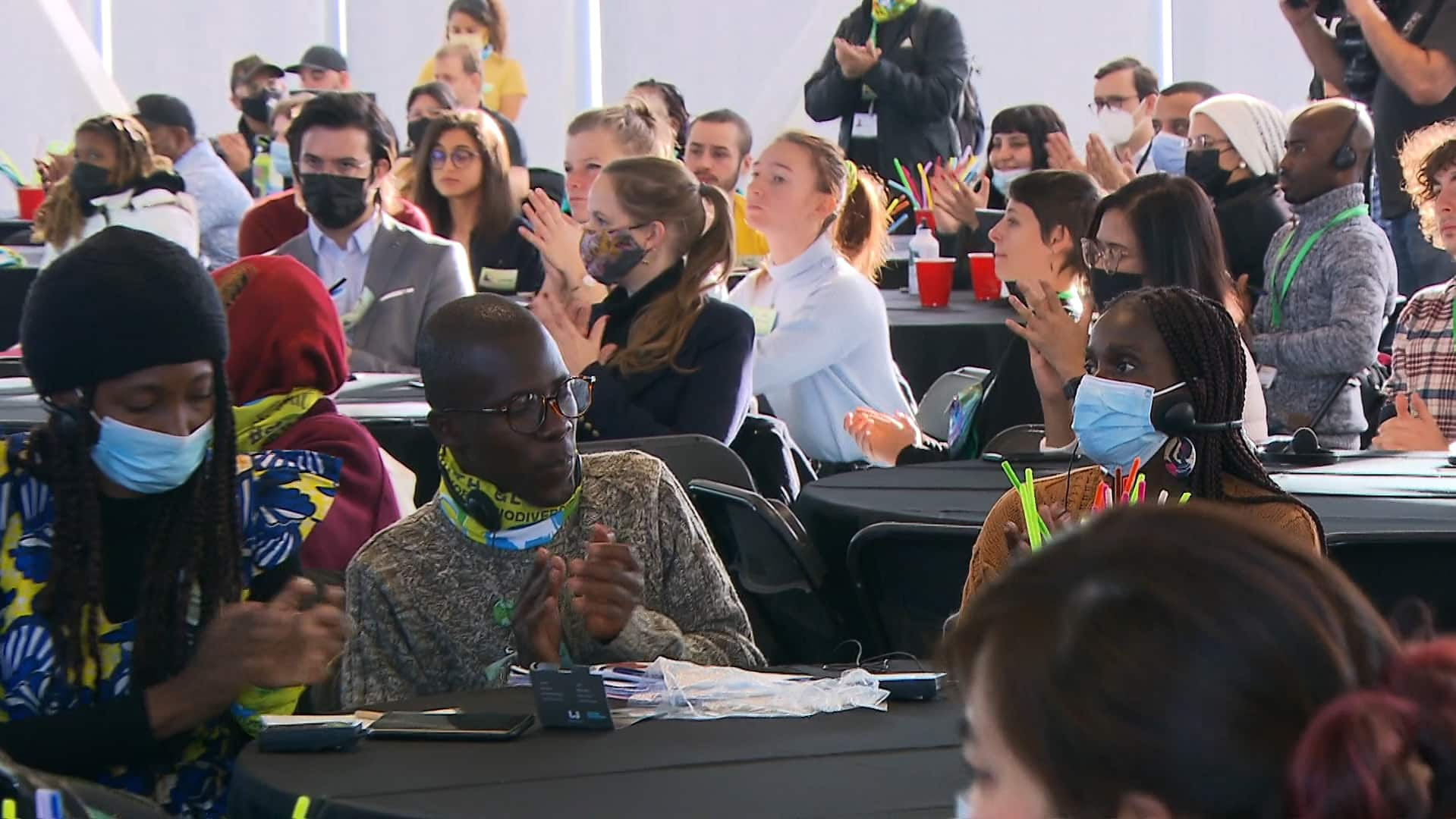

WATCH | What young leaders want to see at COP15:

More than 300 young people from around the globe are in Montreal to talk about biodiversity and how they can effect change as part of the two-day COP-15 Youth Summit.

Research shows how valuable Canadian forests are

In recent years, scientific research employing newly available satellite data (among other methods) has painted a clearer picture of just how valuable Canada’s forests are. The area of the Seal River Watershed is one of the most carbon-rich landscapes in Canada, part of a swath of carbon-rich forests and wetlands extending from Northern Ontario into Manitoba.

That carbon is tied up in plants, trees, and most importantly, layers upon layers of dead organic material built up over centuries and stored in the soil.

Keeping that carbon where it is, scientists say, is crucial on a warming planet. If that carbon is disturbed and ends up escaping into the atmosphere, it will trap more heat and escalate the climate crisis.

“We have amongst the most important space of intact ecosystems remaining on the planet,” Snider said.

“We retailer an incredible, jaw-dropping quantity of carbon. And so there is a accountability globally, many would argue, by way of defending these vital locations.”