Prime Minister Justin Trudeau took the stand at the Emergencies Act inquiry — here’s what we learned | 24CA News

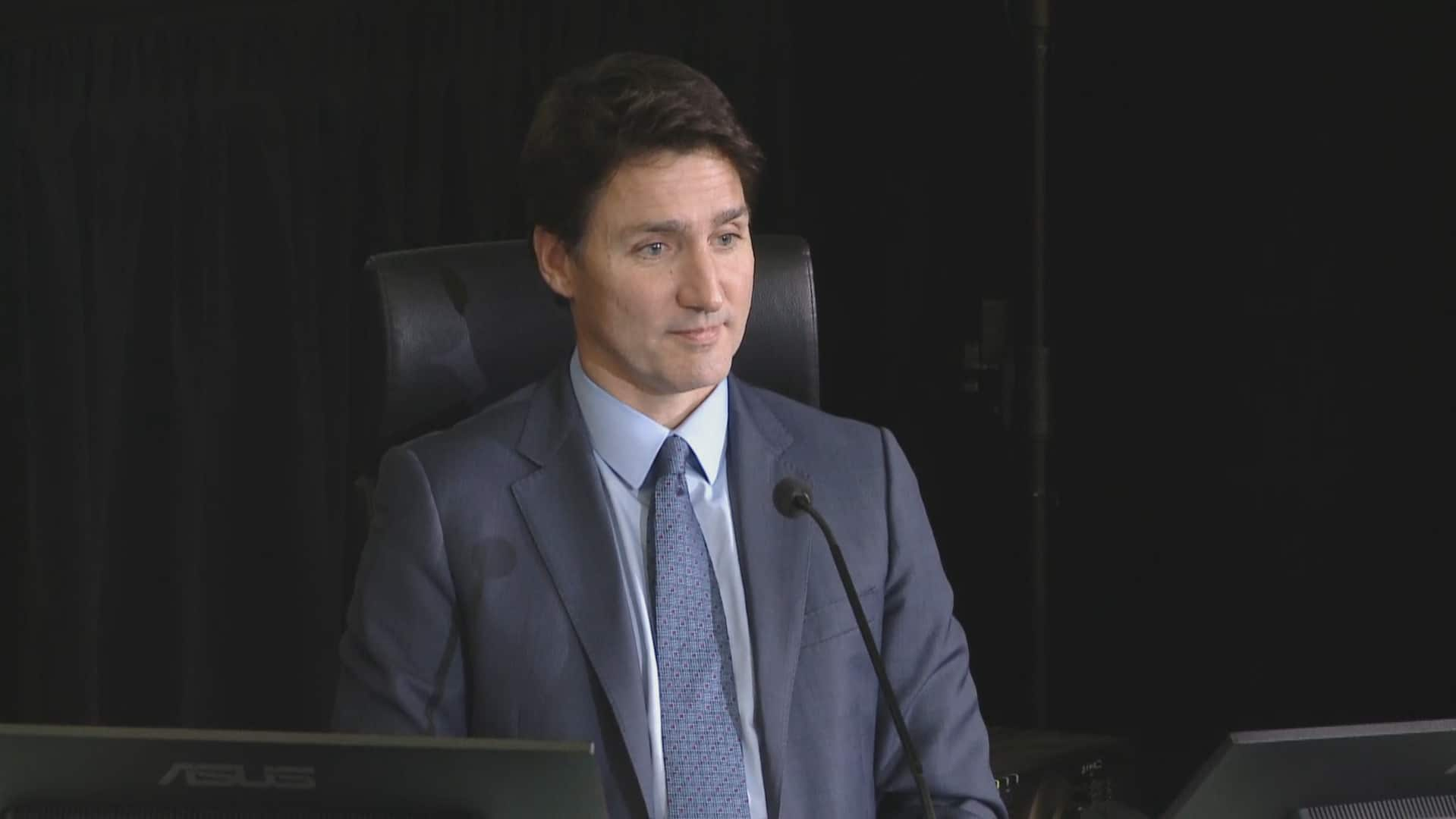

The dwell testimony portion of the Public Order Emergency Commission got here to a detailed on Friday when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau took the stand. His keenly anticipated look earlier than the fee inquiry provided many telling moments and pointed criticisms.

The fee was launched to look at the federal government’s invocation of the Emergencies Act to deal with the anti-vaccine mandate protests that swarmed the downtown streets of the nation’s capital final winter.

As fee counsel Shantona Chaudhury identified Friday morning, the fee had heard mountains of proof earlier than Friday however was lacking one essential perspective — that of the prime minister who invoked the Emergencies Act again in February.

Here are 5 key takeaways from his testimony.

Has the ‘Kraken’ been unleashed?

One line of questioning by Chaudhury targeted on whether or not the prime minister fearful that invoking the act, even for a brief time, would make future governments extra probably to make use of it.

“But do you worry about the floodgates aspect of this, that having done this, you’ve now maybe unleashed the Kraken?” she requested the prime minister.

Citing previous demonstrations by Indigenous and environmental teams, Chaudhury stated the act of protest is commonly a messy affair that can contain interference with vital infrastructure.

“So what stops this from being used against that?” she requested.

In response, Trudeau stated invoking the act wasn’t one thing his authorities was desperate to do.

During his testimony earlier than the Emergencies Act inquiry, Prime Minister Trudeau is requested whether or not invoking the Emergencies Act will open the ‘floodgates’ and encourage future use.

Trudeau stated that future governments “are likely to look at this experience” and resolve that it is not price invoking the act — though legal guidelines are on the books to information its use and guarantee thresholds are met.

“It would be [a] worse thing for me to say, even though the thresholds have been met, even though it is needed and necessary, we’re not going to do it because someone might abuse it or overuse it in the years to come,” he stated.

“When there’s a national emergency and serious threats of violence to Canadians, and you have a tool that you should use, how would I explain it to the family of a police officer who was killed?

“Or a grandmother who obtained run over attempting to cease a truck or … a protester who was killed?”

Criticism of the OPS Feb. 13 plan

The prime minister was dismissive when asked about a plan the Ottawa Police Service (OPS) had to clear the protests.

As the commission had heard previously, the Ottawa Police Service, the Ontario Provincial Police and the RCMP had come together to craft an operational plan around Feb. 13.

“We heard in testimony right here that there was a plan on the thirteenth that the Ottawa Police Service pulled collectively,” he said. “I’d suggest individuals check out that precise plan, which wasn’t a plan in any respect.”

During his testimony at the Emergencies Act inquiry, the prime minister highlights weak planning from Ottawa Police Services to end the convoy protests.

Trudeau said the plan involved using liaison officers to shrink the perimeter of the Ottawa protest “a bit of bit,” but key features of the plan — such as how police officers would be deployed and what resources would be needed — were left “to be decided later.”

“It was not, even in probably the most beneficiant of characterizations, a plan for the way they had been going to finish the occupation in Ottawa,” he said.

Review the plan? ‘We can’t’

Sujit Choudhry, counsel for the Canadian Constitution Foundation, didn’t let the prime minister’s comments about the OPS plan go unchallenged.

Pointing to the plan, he noted that the document had been heavily redacted.

“It’s inside your authorized authority to instruct your counsel to take away these redactions for the sake of the transparency of this fee,” he said. “Sir, would you rethink that request?”

The Government of Canada objected to Choudhry’s question, arguing that any decision to lift those redactions would have to be carefully considered.

“Prime minister, can I put it to you this manner?” Choudhry asked. “You stated we should always learn the plan, however I believe you’d agree we won’t.”

Trudeau says interpretation of 2 acts that matters

Trudeau also spoke about the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), its mindset and the challenges it faced during the protests.

In an interview with commission counsel that took place before he testified in person, Trudeau said CSIS didn’t have the “proper instruments, mandate and even mindset” to deal with the protesters.

A key point of contention during the inquiry has to do with how Canadian laws — specifically the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act and the Emergencies Act — define threats to national security.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told the Commission’s lawyer that the decision to invoke the Emergencies Act was taken based on the definition of it that states that there were ‘activities supporting the threats or acts of serious violence, threat of serious violence, for political or ideological goals.’

The declaration of a public order emergency under the Emergencies Act relies on the definition of threats to the security of Canada contained in the CSIS Act.

That definition cites harm caused for the purpose of achieving a “political, spiritual or ideological goal,” espionage, foreign interference or the intent to overthrow the government by violence.

In past testimony to the inquiry, the head of CSIS testified he doesn’t believe the protest met the definition of a national security threat under the CSIS Act — but said the Emergencies Act’s definition is broader.

Chaudhury pressed the prime minister to state whether the demonstrations constituted such a threat under the CSIS Act.

“Those phrases within the CSIS Act are used for the aim of CSIS figuring out that they’ve authority to behave towards a person, a gaggle or a selected plot … for instance,” Trudeau said.

But the decision to invoke the Emergencies Act ultimately falls on the government, not CSIS, he said.

And while one act leans on the definition laid out in the other, Trudeau said, CSIS was only one institution among many — including the RCMP, Transport Canada and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada — offering input on that decision.

On Friday, Trudeau said “the context and the aim” of the two laws are “very completely different.” He said his government would review the definition of a national security threat differently from “the intentionally slender body that CSIS is allowed to have a look at.”

“There has been a little bit of back-and-forth at this fee on whether or not these phrases are completely different, or will be learn in a different way, or are broader once they’re utilized in a public order emergency than [when] they’re used for the CSIS,” the prime minister said. “It’s not the phrases which are completely different. The phrases are precisely the identical in each instances.

“The question is, who’s doing the interpretation? What inputs come in and what is the purpose of it?

“And the aim of it for this level was to have the ability to give us … particular short-term measures, as outlined within the Public Order Emergency Act, that might put an finish to this nationwide emergency.”

What constitutes a peaceful protest?

Pointing to a call Trudeau had with then-Conservative Party interim leader Candice Bergen, Chaudhury brought up the importance of balance — between allowing people opposed to government policies to be heard and setting a precedent that says a blockade on Ottawa’s Wellington Street can change those policies.

“Using protests to demand modifications to public coverage is one thing that I believe is worrisome,” the prime minister said initially.

Trudeau soon clarified that statement, saying a protest against a government decision to shut down a safe injection site would also constitute advocating for a change in public policy.

The usual way of protesting, he said, is to persuade voters that a government policy is wrong — enough voters to convince governments to change course. Such protests, he said, can be effective in creating change in a democracy.

“But there’s a distinction between occupations and, you understand, saying we’re not going till this has modified in a approach that’s massively disruptive and doubtlessly harmful,” Trudeau stated.