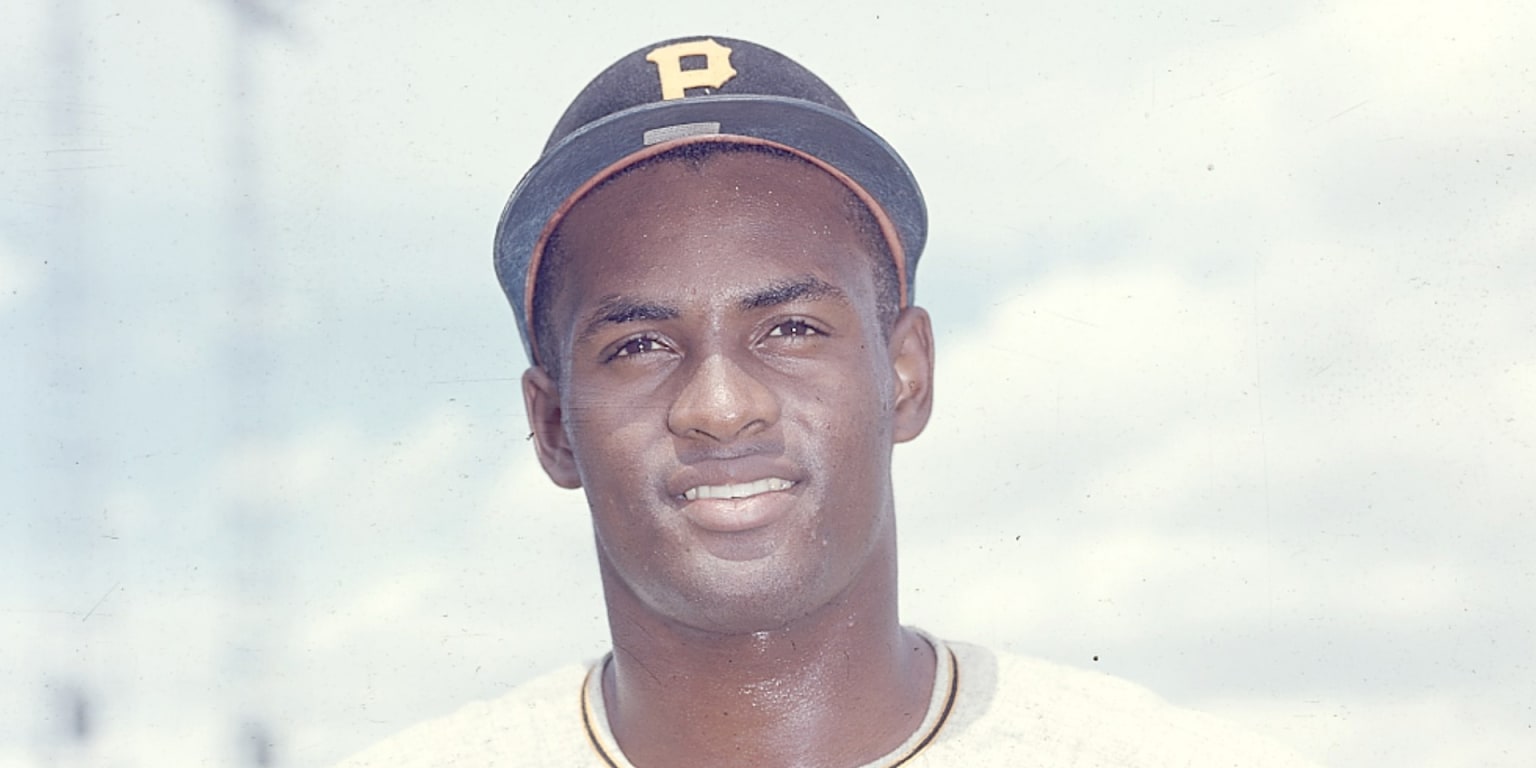

Clemente continued what Robinson started

On the event of the fiftieth anniversary of the tragic loss of life of Roberto Clemente, we current this text beforehand revealed on LasMayores.com and MLB.com.

For 50 years, Roberto Clemente’s legacy has been largely outlined by the ultimate act of his life. When the aircraft he chartered to ship provides to earthquake victims in Nicaragua crashed off the coast of his native Puerto Rico shortly after takeoff on New Year’s Eve 1972, Clemente’s status as a selfless humanitarian grew to become legend.

“Obviously, everyone knows what he did on the field, but off the field, the work he did to help the people — not only in Puerto Rico, but in other Latin countries — this guy is unbelievable,” mentioned Cardinals catcher and Puerto Rico native Yadier Molina. “You can learn from it.”

Clemente, the primary participant from Latin America inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, can also be remembered as a magnificently proficient baseball participant. During his 18-year profession with the Pirates, Clemente was a two-time World Series champion, 12-time Gold Glove Award winner in proper subject and 15-time All-Star. The 1966 National League MVP was additionally the primary Latin American participant to achieve the hallowed 3,000-hit mark. Yet numbers hardly do justice to the exhilarating sight of Clemente tearing across the bases or his breathtaking throws from proper subject.

On Roberto Clemente Day, which coincides with the beginning of Hispanic Heritage Month within the U.S., we keep in mind Clemente’s altruism and his athletic prowess. But there’s one other component of Clemente’s legacy that deserves acknowledgment, and it’s the method he stood as much as bigotry and racism all through his profession within the hopes that those that got here after him wouldn’t should.

Clemente arrived within the Major Leagues in 1955, eight years after Jackie Robinson grew to become the primary Black participant within the historical past of the American and National Leagues, and 9 years earlier than President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into regulation. It appears becoming that Clemente made his debut in opposition to Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers, as he would proceed the battle for racial equality throughout the recreation.

Being Afro-Latino made Clemente topic to Jim Crow legal guidelines, notably in Fort Myers, Fla., the place the Pirates held Spring Training. Like the opposite Black gamers of his period, Clemente was not allowed to remain on the identical accommodations or share meals together with his white teammates at eating places. Yet legalized segregation was international to Clemente, who had grown up in a way more built-in society in Puerto Rico.

“My mother and father never taught me to hate anyone, or to dislike anyone because of their race or color,” Clemente mentioned in a tv look in October 1972, which is taken into account his last interview with English-language media. “We by no means talked about that.”

In that interview, the previous U.S. Marine Corps reservist described changing into so indignant about having to attend on the workforce bus whereas his white teammates dined that he demanded Pirates basic supervisor Joe Brown present the workforce’s Black gamers with a automotive of their very own to journey in.

Clemente additionally had no drawback calling out the mainstream media, which anglicized his identify to “Bob” regardless of his objections and quoted him utilizing phonetic spelling in abhorrent mockery of his accent. He challenged stereotypes about Latino gamers whereas demanding to be handled with respect and dignity, at the same time as a few of his friends urged him to maintain his head down and stay quiet.

“They told me, ‘Roberto, you better keep your mouth shut because they will ship you back,’” he recalled. “I said, ‘I don’t care one way or the other. If I’m good enough to play here, I have to be good enough to be treated like the rest of the players.’”

“[Clemente’s] influence on the culture of leadership in baseball is what gets lost,” says Adrian Burgos Jr., professor of historical past on the University of Illinois, who focuses on the participation of minorities in American skilled sports activities. “Clemente was a figure who was not satisfied, was not acquiescent to those who refused to treat his people, Black and Latino, less than [they] treated the other individuals in baseball.”

It wasn’t till 1960, his sixth season within the Major Leagues, that Clemente’s profession actually took off. He was chosen to his first All-Star Game and he helped the Pirates beat the Yankees in a seven-game World Series. Yet at the same time as he rose to stardom, Clemente remained a humble man who noticed himself, as he put it, as belonging to “the common people of America.”

Clemente’s fierce satisfaction in his Puerto Rican roots by no means wavered. It was by no means extra evident than in 1971, when he slashed .414/.452/.759 within the Fall Classic to turn into the primary Latin American participant to be acknowledged with the World Series MVP Award. His efficiency included two dwelling runs, the second a solo shot within the fourth inning of Game 7 that proved essential within the 2-1 win that gave Pittsburgh the sequence victory over Baltimore.

To these following in Latin America, what Clemente did instantly after — ask his mother and father in Puerto Rico for his or her blessing, in Spanish, on nationwide tv — was simply as heroic. In what he referred to as the “biggest day of his life,” Clemente asserted that he was nonetheless, above all, puertorriqueño.

“He was not embarrassed about being Puerto Rican, Latino, Black,” Red Sox supervisor and Puerto Rico native Alex Cora mentioned in Spanish. “On national television, he asked for a moment to speak Spanish. No one does that. He taught us resolve and conviction. In many ways, he showed the world that we have to fight for what we believe in and we have to stand up for our rights, and he did it the right way.”

Clemente’s efforts to make the sport extra welcoming for folks like him is basically why he’s a hero to the legions of Latin American gamers who adopted in his footsteps and who get to put on their names on the backs of their jerseys full with accent marks and tildes. It’s why so a lot of MLB’s Puerto Rican gamers have been thrilled to affix the Pirates in carrying Clemente’s No. 21 on Roberto Clemente Day 2020, a chance that MLB has prolonged to all gamers.

Yet maybe nobody reveres Clemente greater than his pal and former Pirates teammate, Panamanian-born catcher Manny Sanguillén.

Clemente and Sanguillén have been a part of the primary all-Black and Latino lineup in AL/NL historical past on Sept. 1, 1971. Clemente, Sanguillén remembers, would usually say that he strove for excellence as a result of he wished to create a path to the Majors for others like him by demonstrating gamers from Latin America had the abilities and make-up to be difference-makers on the sector.

“I have to take care of myself and play well so that one of these days, the Major Leagues will be full of Latinos,” Sanguillén remembers Clemente saying.

Clemente, who was 38 on the time of the deadly aircraft accident, didn’t reside lengthy sufficient to see his imaginative and prescient fulfilled. But his affect endures.

“My dad taught me the game that way,” Mets shortstop and Puerto Rico native Francisco Lindor mentioned of Clemente’s affect on his life. “Being aggressive, having fun, and then after you do all that, you go out there and help others and you become a great person off the field.”

So on Roberto Clemente Day, we honor an ideal humanitarian and an awfully gifted baseball participant. But we additionally pay tribute to a person whose dedication to equity, equality and inclusion modified the tradition of our recreation for the higher.